The 'Jew' of cinema

Haaretz

December 17, 2010

By Ariel Schweitzer

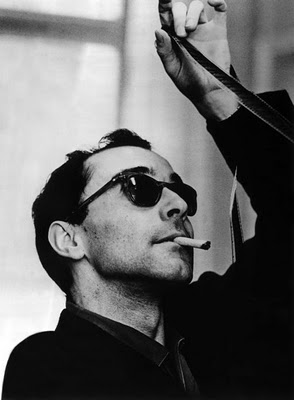

The recent announcement that filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard's is to receive an honorary Oscar has ignited the controversy over his allegedly anti-Semitic and anti-American views, and his unwillingness to see the Jews in any position but that of the victim.

Professor Philip Watts from Columbia University will speak in April about Godard, WWII, the Jews and the Holocaust at CHGS's lecture series, "Alternative Narratives or Denial?" Professor Watts will examine portions of Godard's work and discuss how his history may have shaped and informed his cinematographic choices which have led to the anti-Semitic charges. More information about the lecture series coming in January.

The brouhaha that erupted in the United States and France recently over the decision to grant Jean-Luc Godard an honorary Academy Award - replete with accusations that Godard is anti-American, anti-Israel and even anti-Semitic - marks a new climax in the film director's convoluted relationship with American culture, with the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and with Jewish issues.

These fraught relations have been characterized by misunderstandings and confusion with respect to political critique and to philosophical and metaphysical questions, responsibility for which lies with both Godard and critics who have interpreted his work over the years.

Godard, who turned 80 this month, was not always critical of American culture and politics. Like many members of his generation who witnessed Europe's liberation by U.S. armed forces, he was exposed to the plethora of movies, jazz and other elements of American popular culture that flooded the continent after the war. At the time, the United States was seen as a young, dynamic nation, in contrast to the conservative, staid European society, which had been "tarnished" in moral terms by World War II. As a critic for the magazine Cahiers du cinema, Godard extolled American film and saw its great creators - Alfred Hitchcock, John Ford and Howard Hawks - as "auteurs" even before they were recognized as such in the States.

Moreover, Godard's early films, like those of many of his fellow directors of the French New Wave, were homages to American cinema. "Breathless," his first feature-length film, in 1959, is a variation on American gangster movies; 1961's "Une femme est une femme" is a direct reference to musical comedy.

This viewpoint began to change with the politicization of Godard's cinema in the mid-1960s. In films such as "Pierrot le fou" (1965 ), "2 or 3 Things I Know About Her" (1967), and "Week End" (1967 ), Godard mapped modern consumer society by means of its array of symbols. His criticism was directed at the time not only at French society, but also at the United States, cradle of the capitalist system, which he accused of economic and cultural imperialism.

In 1967 Godard also directed a segment in the collaborative film "Far from Vietnam," which slammed America's military involvement beyond its borders. This work heralded his abandonment of traditional cinema, the notion of the director as "auteur," and a decision to work from then on outside the established industry.

After the riots between students, workers and police in Paris in May '68, Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin, a political activist with a Marxist orientation, founded a political film collective named after the Soviet director Dziga Vertov. In this framework, Godard had directed some 10 films by 1972. One of the topics he dealt with was the Third World and his struggle against Western imperialism. This was also the moment when Israel entered his oeuvre - as America's representative in the Middle East and the oppressor of the Palestinians, whom Godard identified with the Third World and with his support for liberation and independence.

In 1970, Groupe Dziga Vertov, with funding from by the Arab League, went to Jordan to shoot a pro-Palestinian propaganda film called "Until Victory." They spent several weeks following the training of Palestinian guerrillas. Godard returned to France with the footage (shot in 16mm ) and embarked on the editing. But then came news of the Black September events, in which the army of Jordan's King Hussein massacred thousands of Palestinians (including many who had been filmed by Groupe Dziga Vertov ), in order to prevent a Palestinian takeover of the Hashemite kingdom.

The shocked Godard realized that he might be lacking a sufficient understanding of the complexity of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and inter-Arab relations and decided to abandon the film. In 1974, however, he incorporated footage from it into a new film, which he edited with video technology for the first time. In this work, "Ici et ailleurs" ("Here and Elsewhere" ), Godard looked at how Third World struggles are perceived in France and how the Israeli-Palestinian conflict could serve to illuminate problems of class relations, coercion and exploitation in the Western world. It includes an outrageous visual analogy between the figures of Golda Meir and Hitler (to a soundtrack of the Kaddish prayer being recited for victims of the Holocaust ) - an image whose meaning is difficult to mistake: The Jew, erstwhile victim, is seen as the oppressor of the Palestinians. That image, which in the 1970s barely caused a stir (also because of the film's limited distribution ), over time became a sort of black hole, "absorbing" all the claims of those who consider Godard to be an anti-Semite.

In fact, the first to detect such feelings in Godard was actually Francois Truffaut, his close friend from the French New Wave period during the 1960s. In 1973, in a sharp letter that spelled the end of their friendship (and which became public only in 1988 , after Truffaut's death), Truffaut mentioned that Godard used to call his producer, Pierre Braunberger, a "filthy Jew." Truffaut also mocked Godard's militant political views: "After all, those who called you a genius, no matter what you did, all belonged to that famous trendy left. But you - you're the Ursula Andress of militancy; you make a brief appearance, just enough time for the cameras to flash. You make two or three duly startling remarks and then you disappear again, trailing clouds of self-serving mystery."

Focus on the Holocaust

In the '80s Godard's preoccupation with the Israeli-Palestinian conflict expanded into a metaphysical discussion of the Jewish question, and the Holocaust became a central theme in his work. He drew upon the teachings of French philosopher Gilles Deleuze, who held that the emergence of the death camps was the formative event of the 20th century, and that the crisis in Western society, epitomized by Auschwitz, was also reflected in the concurrent birth of modern cinema.

In this spirit, Godard dealt almost obsessively with the experience of the camps. In his "Histoire(s) du cinema" (1989), he relates to cinema's treachery in serving the propagandist machinery of the Third Reich, although he also mentions that cinema "saved the honor of reality" by documenting the atrocities of the war as soon as the Nazi camps were liberated. He expressed an identification with the fate of the Jewish people, and even proclaimed himself "juif du cinema" - reflecting the sentiment that he was persecuted and banned from his home, indeed from his continent, and sentenced to perpetual exile. (In his letter, Truffaut also mocked Godard's tendency to present himself as a victim, even early on in his career. )

In this connection Godard resorted to certain analogies that began to arouse discomfort, to say the least. In the 1995 audiovisual essay "JLG/JLG - autoportrait de decembre," he dealt with the figure of the "Musulman," the living dead of the concentration camps, and emphasized that the root of that word is "Muslim." In view of his preoccupation with the Palestinian tragedy, that statement was once again interpreted as an effort to make an analogy between the fate of the Jews in the Holocaust and that of the Palestinians under the Israeli occupation.

Godard never confirmed such interpretations. He generally tends to present his oeuvre as poetic, associative art, but it is precisely this poetic quality that leaves his films open to interpretation and misunderstanding. What can be seen as the filmmaker's legitimate criticism of the Israeli occupation and his support for the Palestinians' struggle for freedom and independence (which he was among the first movie directors to take an interest in ) lose their validity when Godard equates - even if obliquely - the fate of the Palestinians with the fate of the Jews in the Holocaust. The Palestinian tragedy is serious enough and does not need the "support" of such comparisons, which detract from consideration of the specific, political nature of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and even spill over into the amorphous and fraught territory of theology and myth.

Moreover, it seems that in recent years Godard has been making deliberate use of provocation in order to stay in the headlines at a time when his films no longer resonate with a wide audience. His latest effort, "Filme socialisme," which came out this year and was seen in France by only 25,000 people, decries the death of the socialist utopia in the Europe of the third millennium, portrayed as a continent in crisis, which celebrates its decline as in the last days of Pompeii. The setting of the film, and its main metaphor is a pleasure boat that cruises between Mediterranean cities. Among the passengers is a Jewish capitalist, Goldberg, whose name Godard takes the trouble of translating literally into French as "gold mountain."

About a year before the film came out, Le Monde ran a long piece on the Jewish themes in Godard's work, which included testimony from Alain Fleischer which provoked a huge controversy in France. Fleischer, who directed the film "Fragments of Conversations with Jean-Luc Godard" (2007 ), said the Godard equated Palestinian suicide bombers with Jews who "sacrificed" themselves in the gas chambers in the name of the establishment of the State of Israel. Godard has never confirmed this, but he has also, as is quite typical, never denied it.

No middle ground

Godard is without a doubt anti-Zionist, but moreover he instills his political vision with a metaphysical dimension of the sort that is incapable of accepting the figure of the Jew as anything but a victim. In the filmmaker's view, the moment we are talking about a Jew who is an Israeli - and thus someone who no longer can claim to be a victim, per se - he necessarily becomes an executioner. Between the extremes of victim and executioner there is no middle ground, of the kind that would illuminate the political conflict from a slightly more complex perspective.

In a similar way, throughout his career, Godard developed an ideal, utopian image of Diaspora Judaism as universal, humane and spiritual, and an image of Zionism - and by implication, Israeliness - as isolationist, self-absorbed and aggressive. This dichotomy, which is at the heart of Godard's rejection of Jewish nationalism, ignores the fact that Zionism, at least at its inception, drew its inspiration in the late 19th century from the universal and modern ideas of the Enlightenment (that is, normalization of the Jewish condition, national liberation, socialism and humanism ), whereas during many chapters in its history, Diaspora Judaism was (and to a certain extent is still today ) characterized by community, if not isolationism.

Godard's obsession with Jewish matters was given riveting expression in his film "Notre musique" (2004 ). In the film, a Haaretz correspondent (played by Sarah Adler ) comes to Sarajevo to interview the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish (played by the late poet himself ). Darwish tells her that the Palestinians are lucky that their conflict is with the Jews, since the world takes an ongoing interest in the Jews and thus is also interested in the fate of the Palestinians. "You handed us a defeat and granted us glory at the same time," Darwish adds. "You are our ministry of propaganda, because the world is interested in you, not in us. I have no illusions on that score."

Does not such a comment - which Godard could after all have omitted from the film - attest to a modicum of awareness regarding Europe's problematic perception of the Middle East conflict, which is tainted by no small amount of self-righteousness, guilt feelings (over the Holocaust, and also over the Continent's colonial past ), and occasionally also dogmatism?

Dr. Ariel Schweitzer is a film historian and critic for the French magazine Cahiers du cinema.

This story is by: Ariel Schweitzer

Showing posts with label Godard. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Godard. Show all posts

Monday, December 20, 2010

Tuesday, October 19, 2010

Jean-Luc Godard, anti-Semite?

Bruno Chaouat, director

It was recently announced by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences that Jean-Luc Godard, the Swiss-French filmmaker, will receive an honorary Oscar at this year's ceremony (see article from Jewish Journal posted by CHGS on October 16th, 2010). With this announcement came articles, blog posts and op-eds referring to the filmmaker's real or alleged anti-Semitism.

It is important for the world of scholarship to connect with current events, and we post these articles in order to examine these events with a sense of nuance and depth that the complexity of culture and history requires. While journalism often makes the complexity of the world accessible at the cost of simplifying it, the mission of an academic center such as ours is to approach this complexity with rigor, scientific and intellectual integrity and without sensationalizing.

It is particularly timely that Professor Philip Watts from Columbia University will speak in April about Godard, WWII, the Jews and the Holocaust at CHGS's lecture series, "Alternative Narratives or Denial?" Professor Watts will examine portions of Godard's work and discuss how his history may have shaped and informed his cinematographic choices which have led to the anti-Semitic charges.

We look forward to this exchange, and will continue to look at current events and provide a platform to lead us into deeper inquiry beyond the headlines.

It was recently announced by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences that Jean-Luc Godard, the Swiss-French filmmaker, will receive an honorary Oscar at this year's ceremony (see article from Jewish Journal posted by CHGS on October 16th, 2010). With this announcement came articles, blog posts and op-eds referring to the filmmaker's real or alleged anti-Semitism.

It is important for the world of scholarship to connect with current events, and we post these articles in order to examine these events with a sense of nuance and depth that the complexity of culture and history requires. While journalism often makes the complexity of the world accessible at the cost of simplifying it, the mission of an academic center such as ours is to approach this complexity with rigor, scientific and intellectual integrity and without sensationalizing.

It is particularly timely that Professor Philip Watts from Columbia University will speak in April about Godard, WWII, the Jews and the Holocaust at CHGS's lecture series, "Alternative Narratives or Denial?" Professor Watts will examine portions of Godard's work and discuss how his history may have shaped and informed his cinematographic choices which have led to the anti-Semitic charges.

We look forward to this exchange, and will continue to look at current events and provide a platform to lead us into deeper inquiry beyond the headlines.

Labels:

anti-Semitism,

CHGS,

Godard,

homepage,

Watts

Monday, October 11, 2010

Is Jean-Luc Godard an anti-Semite?

CHGS will explore this question more in depth during our lecture series "Alternative Narratives or Denial?" in March and April of 2011. check our web site for updates and information coming soon.

October 6, 2010

Is Jean-Luc Godard an anti-Semite?

Jean-Luc Godard to get honorary Oscar, questions of anti-Semitism remain

By Tom Tugend

JewishJournal.com

Hollywood's Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences has announced that it will bestow an honorary Oscar on iconic Swiss-French filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard on Nov. 13.The announcement has raised a new question and revived an old one. First, will Godard show up to accept the award? Second, is he an anti-Semite?

Both questions can be answered with a categorical "maybe yes or maybe no." Godard, who will mark his 80th birthday in December, is one of the originators, and among the last survivors, of the French New Wave cinema, which he helped kick-start in 1960 with "Breathless," still his best-known work.

He and his cohorts, among them Francois Truffaut and Eric Rohmer, rebelled against the traditional French movie, and later against all things Hollywood.

The New Wave elevated the role of the director as the sole auteur of a movie and viewed film as a fluid audiovisual language, freed of the constraints of formal story lines, plot, narration and sequence.

As Godard put it, "I believe a film should have a beginning, a middle and an end, but not necessarily in that order."

To a small coterie of cinephiles and most professional film critics, especially in Europe, Godard is considered the ultimate cinematic genius. To others, his films often seem insufferably opaque and incomprehensible.

In the 50 years since his film debut, Godard has proven his vigor and inventiveness in 70 features and is credited with strongly influencing such American directors as Martin Scorsese, Quentin Tarantino and Steven Soderbergh.

Godard's long career has been marked by constant artistic disputes and charges of anti-Semitism and anti-Zionism, as noted in three biographies: "Godard: A Portrait of the Artist at 70" (2003) by American professor Colin MacCabe; "Everything Is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard" (2008) by Richard Brody, an editor and writer for the New Yorker; and "Godard" by film historian Antoine de Baecque.

The last was published in March in French and is not easily available. Material used in this article was drawn from reviews and analyses of the book.

The early seeds of Godard's alleged anti-Semitism and acknowledged anti-Zionism may have been planted in the home of his affluent Swiss-French Protestant family.

In a 1978 lecture in Montreal, he spoke of his family's own political history as World War II "collaborators" who rooted for a German victory, and of his grandfather as "ferociously not even anti-Zionist, but he was anti-Jew; whereas I am anti-Zionist, he was anti-Semitic."

Godard validated his anti-Israel credentials in 1970 by filming "Until Victory," depicting the "Palestinian struggle for independence," partially bankrolled by the Arab League.

The project was eventually aborted, but Godard used some of the footage in his 1976 documentary, "Ici et ailleurs" ("Here and Elsewhere"), contrasting the lives of two families -- one French and one Palestinian.

In it, Godard inserted alternating blinking images of Golda Meir and Adolf Hitler, and suggested, in reference to the 1972 Munich Olympics massacre, that "before every Olympic finale, an image of a Palestinian [refugee] camp should be broadcast."

Biographer Brody, like the other authors, is an ardent admirer of Godard the artist, but he notes that in the filmmaker's later work, "Godard's obsession with living history ... has brought with it a troubling set of idées fixes, notably regarding Jews and the United States."

Godard has been able to combine both targets in his attacks on Hollywood, and, of course, the Jews who run it.

He has always been obsessed by the Holocaust, and after the 1993 release of "Schindler's List," the film and its director, Steven Spielberg, became Godard's favorite whipping boys. As in many of his attacks on Hollywood, it is at times difficult to discern whether Godard's hostility is based on artistic differences or anti-Semitism, or a bit of each.

The leitmotif running through Godard's own work is the superiority of "images" as against "texts" or narratives, or, as he puts it, "the great conflict between the seen and the said."

He faults, for instance, Claude Lanzmann's monumental nine-hour film, "Shoah," for its use of personal narratives by survivors and others, and proposes that the Holocaust can only be truly represented by showing the home life of one of the concentration camp guards.

Who is to blame for the Jewish preference of text over image? It is Moses, Godard's "greatest enemy," who "saw the bush in flames and who came down from the mountain and didn't say, 'This is what I saw,' but, 'Here are the tablets of the law.' "

For the untutored layman, unfamiliar with the methods and passions of movie making, this and other Godard pronouncements can take on an Alice-in-Wonderland quality.

A key may be found in a recent London Sunday Times story, in which a reporter interviewed one of Godard's oldest friends, a retired geology professor.

"He [Godard] is on a different level from the rest of us, somewhere between genius and completely round the bend," the professor explained.

Artistic differences aside, there are disturbing instances of Godard's anti-Semitism, particularly directed against some of his closest collaborators. According to the three biographers, at one point Godard called producer Pierre Braunberger, an early supporter of the New Wave filmmakers, a "sale Juif " (filthy Jew).

In another case, when longtime collaborator Jean-Pierre Gorin requested some back pay, Godard noted, "Ah, it's always the same, Jews call you when they hear a cash register opening."

When this reporter submitted some of Godard's anti-Semitic utterances to the Motion Picture Academy and requested comments, the request prompted the following written response:

"The Academy is aware that Jean-Luc Godard has made statements in the past that some have construed as anti-Semitic. We are also aware of detailed rebuttals to that charge. Anti-Semitism is of course deplorable, but the Academy has not found the accusations against M. Godard persuasive.

"The Academy's Honorary Awards are presented in recognition of an individual's extraordinary contributions to the art of the motion picture. The organization intends to bestow an honorary Oscar on M. Godard at its second annual Governors Awards on November 13th."

After a follow-up request as to the source of the "detailed rebuttals," an Academy spokeswoman cited a 2009 article in the Canadian magazine Cinema Scope by Bill Krohn, Hollywood correspondent for the influential French film magazine Cahiers du Cinema, to which Godard and many of the early New Wave directors contributed as film critics.

Krohn took on Brody's biography and accused its author of ideological simplification, biographical reductivism, guilt by association, misinterpretations, hurt self-esteem following a snub by Godard and, all in all, of perpetrating "a hatchet job disguised as a celebration of Godard's genius."

Krohn's critique is quite diffuse and short on specifics, but in one concrete instance he illustrates that the same words can be interpreted in different ways.

Although Godard's exclamation of "filthy Jew" was taken by Braunberger as a deadly insult, Krohn interprets it as affectionate banter between old friends and an allusion to the film "La grande illusion."

Perhaps a better defense of Godard may be found in some of the filmmaker's own projects and views, however erratic they may appear.

Given his family background and pro-Palestinian activism, it would not be surprising if Godard were also a Holocaust denier.

But, on the contrary, he is fixated on the murder of6 million, including some 77,000 Jews living in France, and one of his main charges against Hollywood is that Jewish studio heads could have prevented the Shoah by producing a number of anti-Nazi films in the 1930s.

He has labeled repeated accusations that some of his films equate the Palestinian Nakba (defeat in the 1948-49 war) with the Holocaust as "completely idiotic."

In some of Godard's enigmatic films, the same movie may contain both negative and positive themes. For instance, in his 2001 picture "Éloge de l'amour" (In Praise of Love), Godard attacks Spielberg in particular, and America in general, for its perceived lack of history and culture.

He also inserts the last testament of a notorious French fascist and anti-Semite, but on the other hand, the movie also deals with the quest to restore Nazi-looted art to the rightful Jewish and other owners.

Earlier this year, it was reported that Godard was preparing an adaptation of Daniel Mendelsohn's "The Lost: A Search for Six of Six Million," with Israeli filmmaker Oren Moverman.

In an attempt to get additional input on Godard's character and reputation, this reporter contacted several entertainment industry personalities in Hollywood and abroad.

One was Arthur Cohn, the Swiss film producer and winner of six Oscars, including one for the classic "The Garden of the Finzi-Continis," and an ardent Zionist and Jewish activist. Others were Rabbi Marvin Hier, head of the Simon Wiesenthal Center and multiple Academy Award winner; noted UCLA film historian Howard Suber; and writer-producer Lionel Chetwynd.

In one form or another, each said that he had no personal knowledge of Godard's reputed anti-Semitism.

Spielberg is shooting a film in Europe and was not available for comment. However, Marvin Levy, Spielberg's personal spokesman, responded to a query on how Spielberg had dealt with Godard's personal attacks on him and his films, particularly "Schindler's List."

"I don't recall anything from Steven at that time or through the years," Levy responded. "He may have known about Godard's thoughts on 'Schindler's List,' but I never heard him talk about it. All the acclaim overwhelmed any negatives from anybody. It would have been uncharacteristic of him to get into a confrontation with another filmmaker who didn't like his film."

Attempts to reach Godard through the head of his Swiss production company were unsuccessful. This failure will not surprise anyone who has followed the comedic drama of trying to pin down whether Godard will actually attend the Academy's Governors Awards dinner in November at the Hollywood & Highland Center.

At the same event, producer-director Francis Ford Coppola will receive the Irving G. Thalberg Memorial Award, and, in addition to Godard, actor Eli Wallach and historian-preservationist Kevin Brownlow have been chosen for honorary Oscars.

Despite a flurry of faxes, e-mails and couriered letters, Godard did not respond to the invitation for weeks, until some enterprising British reporters tracked him at his home in the Swiss town of Rolle.

Godard escaped the reporters, but Anne-Marie Mieville, his wife and work partner, said Godard was apparently disappointed that the honor would not be conferred at the main Oscars ceremony next February.

In any case, she said, Godard "is getting too old for this kind of thing. Would you go all that way just for a bit of metal?"

The French newspaper Liberation commented that it might be just as well if Godard stayed home, as his speeches "have become mysterious adventures in the country of language."

Nevertheless, the Academy remains officially upbeat, though hedging its bets by stating carefully that it "intends to bestow an honorary Oscar on M. Godard."

Though he may not like to travel, Godard continues to make new films with considerable vigor. His latest, "Socialism," screened at the New York Film Festival on Sept. 29 and will be shown again on Oct. 8.

Benjamin Ivry, a frequent contributor to the Forward, contributed to this article.

© Copyright 2010 Tribe Media Corp.

All rights reserved. JewishJournal.com is hosted by Nexcess.net. Homepage design by Koret Communications.

Widgets by Mijits. Site construction by Hop Studios

October 6, 2010

Is Jean-Luc Godard an anti-Semite?

Jean-Luc Godard to get honorary Oscar, questions of anti-Semitism remain

By Tom Tugend

JewishJournal.com

Hollywood's Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences has announced that it will bestow an honorary Oscar on iconic Swiss-French filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard on Nov. 13.The announcement has raised a new question and revived an old one. First, will Godard show up to accept the award? Second, is he an anti-Semite?

Both questions can be answered with a categorical "maybe yes or maybe no." Godard, who will mark his 80th birthday in December, is one of the originators, and among the last survivors, of the French New Wave cinema, which he helped kick-start in 1960 with "Breathless," still his best-known work.

He and his cohorts, among them Francois Truffaut and Eric Rohmer, rebelled against the traditional French movie, and later against all things Hollywood.

The New Wave elevated the role of the director as the sole auteur of a movie and viewed film as a fluid audiovisual language, freed of the constraints of formal story lines, plot, narration and sequence.

As Godard put it, "I believe a film should have a beginning, a middle and an end, but not necessarily in that order."

To a small coterie of cinephiles and most professional film critics, especially in Europe, Godard is considered the ultimate cinematic genius. To others, his films often seem insufferably opaque and incomprehensible.

In the 50 years since his film debut, Godard has proven his vigor and inventiveness in 70 features and is credited with strongly influencing such American directors as Martin Scorsese, Quentin Tarantino and Steven Soderbergh.

Godard's long career has been marked by constant artistic disputes and charges of anti-Semitism and anti-Zionism, as noted in three biographies: "Godard: A Portrait of the Artist at 70" (2003) by American professor Colin MacCabe; "Everything Is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard" (2008) by Richard Brody, an editor and writer for the New Yorker; and "Godard" by film historian Antoine de Baecque.

The last was published in March in French and is not easily available. Material used in this article was drawn from reviews and analyses of the book.

The early seeds of Godard's alleged anti-Semitism and acknowledged anti-Zionism may have been planted in the home of his affluent Swiss-French Protestant family.

In a 1978 lecture in Montreal, he spoke of his family's own political history as World War II "collaborators" who rooted for a German victory, and of his grandfather as "ferociously not even anti-Zionist, but he was anti-Jew; whereas I am anti-Zionist, he was anti-Semitic."

Godard validated his anti-Israel credentials in 1970 by filming "Until Victory," depicting the "Palestinian struggle for independence," partially bankrolled by the Arab League.

The project was eventually aborted, but Godard used some of the footage in his 1976 documentary, "Ici et ailleurs" ("Here and Elsewhere"), contrasting the lives of two families -- one French and one Palestinian.

In it, Godard inserted alternating blinking images of Golda Meir and Adolf Hitler, and suggested, in reference to the 1972 Munich Olympics massacre, that "before every Olympic finale, an image of a Palestinian [refugee] camp should be broadcast."

Biographer Brody, like the other authors, is an ardent admirer of Godard the artist, but he notes that in the filmmaker's later work, "Godard's obsession with living history ... has brought with it a troubling set of idées fixes, notably regarding Jews and the United States."

Godard has been able to combine both targets in his attacks on Hollywood, and, of course, the Jews who run it.

He has always been obsessed by the Holocaust, and after the 1993 release of "Schindler's List," the film and its director, Steven Spielberg, became Godard's favorite whipping boys. As in many of his attacks on Hollywood, it is at times difficult to discern whether Godard's hostility is based on artistic differences or anti-Semitism, or a bit of each.

The leitmotif running through Godard's own work is the superiority of "images" as against "texts" or narratives, or, as he puts it, "the great conflict between the seen and the said."

He faults, for instance, Claude Lanzmann's monumental nine-hour film, "Shoah," for its use of personal narratives by survivors and others, and proposes that the Holocaust can only be truly represented by showing the home life of one of the concentration camp guards.

Who is to blame for the Jewish preference of text over image? It is Moses, Godard's "greatest enemy," who "saw the bush in flames and who came down from the mountain and didn't say, 'This is what I saw,' but, 'Here are the tablets of the law.' "

For the untutored layman, unfamiliar with the methods and passions of movie making, this and other Godard pronouncements can take on an Alice-in-Wonderland quality.

A key may be found in a recent London Sunday Times story, in which a reporter interviewed one of Godard's oldest friends, a retired geology professor.

"He [Godard] is on a different level from the rest of us, somewhere between genius and completely round the bend," the professor explained.

Artistic differences aside, there are disturbing instances of Godard's anti-Semitism, particularly directed against some of his closest collaborators. According to the three biographers, at one point Godard called producer Pierre Braunberger, an early supporter of the New Wave filmmakers, a "sale Juif " (filthy Jew).

In another case, when longtime collaborator Jean-Pierre Gorin requested some back pay, Godard noted, "Ah, it's always the same, Jews call you when they hear a cash register opening."

When this reporter submitted some of Godard's anti-Semitic utterances to the Motion Picture Academy and requested comments, the request prompted the following written response:

"The Academy is aware that Jean-Luc Godard has made statements in the past that some have construed as anti-Semitic. We are also aware of detailed rebuttals to that charge. Anti-Semitism is of course deplorable, but the Academy has not found the accusations against M. Godard persuasive.

"The Academy's Honorary Awards are presented in recognition of an individual's extraordinary contributions to the art of the motion picture. The organization intends to bestow an honorary Oscar on M. Godard at its second annual Governors Awards on November 13th."

After a follow-up request as to the source of the "detailed rebuttals," an Academy spokeswoman cited a 2009 article in the Canadian magazine Cinema Scope by Bill Krohn, Hollywood correspondent for the influential French film magazine Cahiers du Cinema, to which Godard and many of the early New Wave directors contributed as film critics.

Krohn took on Brody's biography and accused its author of ideological simplification, biographical reductivism, guilt by association, misinterpretations, hurt self-esteem following a snub by Godard and, all in all, of perpetrating "a hatchet job disguised as a celebration of Godard's genius."

Krohn's critique is quite diffuse and short on specifics, but in one concrete instance he illustrates that the same words can be interpreted in different ways.

Although Godard's exclamation of "filthy Jew" was taken by Braunberger as a deadly insult, Krohn interprets it as affectionate banter between old friends and an allusion to the film "La grande illusion."

Perhaps a better defense of Godard may be found in some of the filmmaker's own projects and views, however erratic they may appear.

Given his family background and pro-Palestinian activism, it would not be surprising if Godard were also a Holocaust denier.

But, on the contrary, he is fixated on the murder of6 million, including some 77,000 Jews living in France, and one of his main charges against Hollywood is that Jewish studio heads could have prevented the Shoah by producing a number of anti-Nazi films in the 1930s.

He has labeled repeated accusations that some of his films equate the Palestinian Nakba (defeat in the 1948-49 war) with the Holocaust as "completely idiotic."

In some of Godard's enigmatic films, the same movie may contain both negative and positive themes. For instance, in his 2001 picture "Éloge de l'amour" (In Praise of Love), Godard attacks Spielberg in particular, and America in general, for its perceived lack of history and culture.

He also inserts the last testament of a notorious French fascist and anti-Semite, but on the other hand, the movie also deals with the quest to restore Nazi-looted art to the rightful Jewish and other owners.

Earlier this year, it was reported that Godard was preparing an adaptation of Daniel Mendelsohn's "The Lost: A Search for Six of Six Million," with Israeli filmmaker Oren Moverman.

In an attempt to get additional input on Godard's character and reputation, this reporter contacted several entertainment industry personalities in Hollywood and abroad.

One was Arthur Cohn, the Swiss film producer and winner of six Oscars, including one for the classic "The Garden of the Finzi-Continis," and an ardent Zionist and Jewish activist. Others were Rabbi Marvin Hier, head of the Simon Wiesenthal Center and multiple Academy Award winner; noted UCLA film historian Howard Suber; and writer-producer Lionel Chetwynd.

In one form or another, each said that he had no personal knowledge of Godard's reputed anti-Semitism.

Spielberg is shooting a film in Europe and was not available for comment. However, Marvin Levy, Spielberg's personal spokesman, responded to a query on how Spielberg had dealt with Godard's personal attacks on him and his films, particularly "Schindler's List."

"I don't recall anything from Steven at that time or through the years," Levy responded. "He may have known about Godard's thoughts on 'Schindler's List,' but I never heard him talk about it. All the acclaim overwhelmed any negatives from anybody. It would have been uncharacteristic of him to get into a confrontation with another filmmaker who didn't like his film."

Attempts to reach Godard through the head of his Swiss production company were unsuccessful. This failure will not surprise anyone who has followed the comedic drama of trying to pin down whether Godard will actually attend the Academy's Governors Awards dinner in November at the Hollywood & Highland Center.

At the same event, producer-director Francis Ford Coppola will receive the Irving G. Thalberg Memorial Award, and, in addition to Godard, actor Eli Wallach and historian-preservationist Kevin Brownlow have been chosen for honorary Oscars.

Despite a flurry of faxes, e-mails and couriered letters, Godard did not respond to the invitation for weeks, until some enterprising British reporters tracked him at his home in the Swiss town of Rolle.

Godard escaped the reporters, but Anne-Marie Mieville, his wife and work partner, said Godard was apparently disappointed that the honor would not be conferred at the main Oscars ceremony next February.

In any case, she said, Godard "is getting too old for this kind of thing. Would you go all that way just for a bit of metal?"

The French newspaper Liberation commented that it might be just as well if Godard stayed home, as his speeches "have become mysterious adventures in the country of language."

Nevertheless, the Academy remains officially upbeat, though hedging its bets by stating carefully that it "intends to bestow an honorary Oscar on M. Godard."

Though he may not like to travel, Godard continues to make new films with considerable vigor. His latest, "Socialism," screened at the New York Film Festival on Sept. 29 and will be shown again on Oct. 8.

Benjamin Ivry, a frequent contributor to the Forward, contributed to this article.

© Copyright 2010 Tribe Media Corp.

All rights reserved. JewishJournal.com is hosted by Nexcess.net. Homepage design by Koret Communications.

Widgets by Mijits. Site construction by Hop Studios

Labels:

anti-Semitism,

Breaking News on the Web,

Godard,

Oscars

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

© Regents of the University of Minnesota. All rights reserved. Equal opportunity educator and employer.