NPR News

by ERIC WESTERVELT

During the Third Reich, Germany's foreign ministry staff across Europe cooperated in the mass murder of Jews and others, according to a government-sponsored study released Thursday in Berlin.

The report says German diplomats during the Nazi era were far more deeply involved in the Holocaust than previously acknowledged. It also shows how West German diplomats after the war worked to whitewash history and create a myth of resistance and opposition to Nazi rule.

Fully Aware And Actively Involved

The report is a devastating indictment of Germany's war-era diplomatic corps, that long cast itself as relatively "clean" of Nazi war crimes and tried to portray any wrongdoing as the result of a few bad actors.

Peter Hayes, a professor at Northwestern University in Evanston, Ill., is one of four historians who co-wrote the nearly 900-page report. He hopes it helps destroy one of the last myths of the Third Reich.

Historians over the last two decades have chronicled the deep complicity of the major institutions of German society -- including big business and universities -- in the crimes of the Nazi regime.

"This is really the last bastion of the notion that high-ranking people in the society could somehow keep themselves separate from what the Third Reich set out to do," Hayes says.

Historians looked in 32 different archives worldwide and interviewed eyewitnesses. The study, commissioned by the government five years ago, shows that German diplomats were not only fully aware of the genocidal policy throughout the war, but they were also actively involved in all aspects of deportation, persecution and genocide of Jews.

After the report's release Thursday, Germany's current foreign minister, Guido Westerwelle, said that the ministry took part "with bureaucratic coolness in the systematic annihilation of European Jews."

An Effort To Rewrite History

One of many pieces of damning evidence included a meeting in late 1944 -- when the war was almost certainly lost for Germany -- of the heads of sections of the foreign ministry. At that gathering, the diplomats talked openly about the extent of the mass murder to date and efforts they were going to make to increase the carnage, even in the fading months of the regime.

Other evidence included a travel reimbursement report from German diplomat Franz Rademacher, the head of the ministry's Jewish affairs section, after a trip to Nazi-occupied Serbia.

"He wrote that the purpose of his visit was the liquidation of the Jews in Belgrade -- right there on the form he submitted to the finance office within the ministry," Hayes says.

Historians have previously uncovered evidence of the foreign ministry's Holocaust complicity. Nazi foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop was hanged for war crimes after the Nuremberg trials.

The study also shows how throughout the 1950s and '60s, the ministry worked hard to try to whitewash its role in mass murder and rewrite history.

Americans, too, at times glossed over Nazi crimes -- especially to gain access to intelligence assets or skilled administrators -- as Cold War realpolitik won out over justice, the report notes.

After the Allies let Germans take the lead in de-Nazification and then relaxed control of West German institutions after 1951, the foreign ministry allowed former Nazis to enter the foreign service in droves. Some of those stained diplomats then helped other Nazis gloss over their reputations.

"Once we turned de-Nazification over to the Germans at end of 1946, then very largely this process became one of mutual exculpation," Hayes says. "People wanted to believe their own arguments about how they'd been seduced by the Nazis into following this regime and so on. Thus they believed their own alibis."

The process accelerated when the Allied occupation ended in 1955, Hayes says. Then even members of the SS -- some with extremely dark pasts -- slipped back into the foreign service.

At the release of the report at the foreign ministry, Westerwelle said the extent of ministry collusion during the Nazi era "shames us" and vowed to make the report's findings part of the training for future diplomats.

He also praised the few staffers who actively opposed the Nazis, including a dozen who were killed for their resistance.

Friday, October 29, 2010

Thursday, October 28, 2010

Pennsylvania Board of Education chairman urges Lincoln to reconsider Siddique tenure

Yesterday we posted an article about Academic Freedom and the Holocaust in regards to the statements made by Kaukab Siddique, associate professor of English and journalism at Lincoln University of Pennsylvania. Today's article deals with the community's reaction to the professor and his statements.

Philadelphia Inquirer

By Jeremy Roebuck

Inquirer Staff Writer

October 28, 2010

The head of the Pennsylvania Board of Education this week joined a growing list of protesters urging Lincoln University to reconsider the tenure of a professor who has questioned the Holocaust and urged the overthrow of Israel's government.

Calling professor Kaukab Siddique's recent statements "disgraceful," board Chairman Joseph M. Torsella called on the Chester County school to repudiate the instructor's views and investigate whether campus resources have been used to support his cause.

"They really ought to take pains to determine to what extent the university - and by extension, public resources - have been used to support this," Torsella said Wednesday. "I'm confident that at the end of the investigation, they will appropriately denounce the substance of the views."

Siddique, 67, found himself in the middle of a media maelstrom last week when video of a speech he gave at an anti-Israel rally went viral on the Internet.

Backed by crowds of chanting demonstrators, the associate professor of English urged people to "unite and rise up against this hydra-headed monster which calls itself Zionism."

His statements at the Washington rally, and nonacademic writings that have surfaced in which he questions the significance of the Holocaust, have drawn scrutiny from the likes of Glenn Beck and Bill O'Reilly - both of whom recently featured the professor on their Fox News programs.

Lincoln officials quickly responded that they were not aware of any instance in which the professor had shared those views in the classroom or at a university-sponsored public forum.

Torsella said that response did not go far enough. In a letter sent to Lincoln President Ivory V. Nelson late Tuesday, he urged the university to investigate whether Siddique had used campus resources to support the Baltimore-based version of the group Jamaat al-Muslimeen, which he leads in support of Muslim communities around the world, or its online newsletter, New Trends Magazine. The magazine's website proclaims that the publication is against racism, Zionism, and imperialism, but also declares that it does not endorse violence of any kind.

Recent writings in the magazine that have been attributed to Siddique refer to the Holocaust as a "myth" and a "story," and articles by other authors express support for the regimes of Saddam Hussein in Iraq, the Taliban in Afghanistan, and Hezbollah in Lebanon. That should raise questions in the minds of university administrators, Torsella said.

"A professor expressing personal opinions (even extraordinarily objectionable ones) on current events is one matter," Torsella wrote. "Denying the Holocaust - a tragic historical fact - is another matter entirely."

Siddique has maintained that his critics have taken his views out of context.

"I am against Israel, not against Jews," he said in an interview with The Inquirer last week. He did not respond to calls or e-mails seeking comment Wednesday.

Philadelphia Inquirer

By Jeremy Roebuck

Inquirer Staff Writer

October 28, 2010

The head of the Pennsylvania Board of Education this week joined a growing list of protesters urging Lincoln University to reconsider the tenure of a professor who has questioned the Holocaust and urged the overthrow of Israel's government.

Calling professor Kaukab Siddique's recent statements "disgraceful," board Chairman Joseph M. Torsella called on the Chester County school to repudiate the instructor's views and investigate whether campus resources have been used to support his cause.

"They really ought to take pains to determine to what extent the university - and by extension, public resources - have been used to support this," Torsella said Wednesday. "I'm confident that at the end of the investigation, they will appropriately denounce the substance of the views."

Siddique, 67, found himself in the middle of a media maelstrom last week when video of a speech he gave at an anti-Israel rally went viral on the Internet.

Backed by crowds of chanting demonstrators, the associate professor of English urged people to "unite and rise up against this hydra-headed monster which calls itself Zionism."

His statements at the Washington rally, and nonacademic writings that have surfaced in which he questions the significance of the Holocaust, have drawn scrutiny from the likes of Glenn Beck and Bill O'Reilly - both of whom recently featured the professor on their Fox News programs.

Lincoln officials quickly responded that they were not aware of any instance in which the professor had shared those views in the classroom or at a university-sponsored public forum.

Torsella said that response did not go far enough. In a letter sent to Lincoln President Ivory V. Nelson late Tuesday, he urged the university to investigate whether Siddique had used campus resources to support the Baltimore-based version of the group Jamaat al-Muslimeen, which he leads in support of Muslim communities around the world, or its online newsletter, New Trends Magazine. The magazine's website proclaims that the publication is against racism, Zionism, and imperialism, but also declares that it does not endorse violence of any kind.

Recent writings in the magazine that have been attributed to Siddique refer to the Holocaust as a "myth" and a "story," and articles by other authors express support for the regimes of Saddam Hussein in Iraq, the Taliban in Afghanistan, and Hezbollah in Lebanon. That should raise questions in the minds of university administrators, Torsella said.

"A professor expressing personal opinions (even extraordinarily objectionable ones) on current events is one matter," Torsella wrote. "Denying the Holocaust - a tragic historical fact - is another matter entirely."

Siddique has maintained that his critics have taken his views out of context.

"I am against Israel, not against Jews," he said in an interview with The Inquirer last week. He did not respond to calls or e-mails seeking comment Wednesday.

Wednesday, October 27, 2010

Academic Freedom and Holocaust Denial

Inside Higher Ed

By Dan Berrett

October 26, 2010

A Pennsylvania English professor whose anti-Israel rhetoric and denial of the Holocaust as a historic certainty have ignited controversy is citing academic freedom as his defense.

Kaukab Siddique, associate professor of English and journalism at Lincoln University of Pennsylvania, appeared last month at a pro-Palestinian rally in Washington, where he called the state of Israel illegitimate. "I say to the Muslims, 'Dear brothers and sisters, unite and rise up against this hydra-headed monster which calls itself Zionism,' " he said at a rally on Sept. 3. "Each one of us is their target and we must stand united to defeat, to destroy, to dismantle Israel -- if possible by peaceful means," he added.

While many professors engage in anti-Israel rhetoric, Siddique is getting more scrutiny because his September comments prompted critics to unearth past statements that the Holocaust was a "hoax" intended to buttress support for Israel -- a position that the professor didn't dispute in an interview Monday with Inside Higher Ed.

Siddique maintained that his comments should be placed in the framework of academic freedom, as an example of a questing mind asking tough questions. He also warned of dire consequences if universities can be intimidated by politicians and outside commentators. "That's freedom of expression going up the smokestack here," he said.

"I'm not an expert on the Holocaust. If I deny or support it, it doesn't mean anything," he said before invoking the firebombing of German cities during World War II and the U.S. bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki as examples of the moral ambiguity of the war. "We can't just sit back in judgment and say those guys were bad and we were the good guys," he said. "I always try to look at both sides.... That's part of being a professor."

Siddique cited as scholarly evidence the work of notorious Holocaust denier David Irving, whom a British judge described as an anti-Semitic neo-Nazi sympathizer. "Irving has for his own ideological reasons persistently and deliberately misrepresented and manipulated historical evidence," High Court Judge Charles Gray wrote in a ruling shooting down Irving's claim of libel against the historian Deborah Lipstadt of Emory University.

The Siddique case isn't the first one in which a tenured academic has been criticized for questioning whether the Holocaust happened. Northwestern University periodically faces debate over Arthur R. Butz, an associate professor of electrical engineering who is a Holocaust denier, but who has avoided the topic in his classes.

Siddique's embrace of Holocaust denial could be treated differently because of what he teaches. Cary Nelson, president of the American Association of University Professors and a staunch defender of the right of professors to take highly unpopular positions, said that academic freedom protects the professor's right to criticize both Israeli policy and the moral legitimacy of the Israeli state. Holocaust denial is another matter entirely, said Nelson.

"Were he an engineering professor speaking off campus, it wouldn't matter," said Nelson in an e-mail. "The issue is whether his views call into question his professional competence. If he teaches modern literature, which includes Holocaust literature from a great many countries, then Holocaust denial could warrant a competency hearing."

Siddique's anti-Israel comments were first seized upon by conservative Christian commentators; links to video of his remarks at the rally appeared on Pat Robertson's Christian Broadcasting Network. Siddique said the firestorm that has erupted has been stoked by allies of Israel, and he says his criticisms of the nation are no more harsh than those espoused by President Carter.

"This is actually a concerted act by the extreme right wing aligned with Israel to destroy someone who spoke out against them," said Siddique.

He said he had received hateful e-mails and phone calls every day since the controversy broke. Some simply bore four-letter words. Others threatened death. "I see this as a tremendous dumbing down of the discourse," he said.

Siddique's statements also prompted a letter from two Pennsylvania state Senators last week who questioned whether the professor had expressed these views in class and what steps were being taken to prevent him from doing so. Both Siddique and the university said he had never broached the subject in class.

Lincoln University sought to distance itself from the professor's comments, calling them "offensive" in a prepared statement, and adding that his "personal views and expressed comments do not represent Lincoln University."

Lincoln is a historically black college that is about 45 miles southwest of Philadelphia. It is one of Pennsylvania's state-affiliated institutions. In the current budget year, Lincoln is receiving more than $13 million in operating money from Pennsylvania, according to the state budget.

The letter from the senators follows a resolution introduced in the state Senate in April that condemns what it calls the resurgence of anti-Semitism on college and university campuses. The resolution calls upon the state's education agencies to "remain vigilant and guarded against acts of anti-Semitism against college and university students," though it recommends no sanctions for those who fail to do so.

State Senator Anthony Williams, who is one of the two who wrote to Lincoln, and who sponsored the resolution, took to the floor of the senate in April to speak on its behalf.

"I come from a community that has felt the sting of oppression and discrimination," said Williams, who is black. "To see that anti-Semitic feelings have evolved in this country on college campuses is not only paradoxical, but it is an oxymoron. It is absolutely polar to the example that universities should be establishing and setting across this great country."

"Armenian Golgotha: A Memoir of the Armenian Genocide, 1915-18" by Grigoris Balakian

Review of new important work about the Armenian Genocide

Copies available for loan at CHGS

Chigago Tribune Book Review

Carlin Romano

Special to the Tribune

"Armenian Golgotha: A Memoir of the Armenian Genocide, 1915-18"

By Grigoris Balakian

Translated by Peter Balakian with Aris Sevag

Alfred A. Knopf. 509 pp. $35

Armenian Golgotha is the astonishing memoir of Father Grigoris Balakian (1876-1934), a work from the 1920s shepherded into English by his great nephew Peter Balakian, the leading American expert on the ARMENIAN genocide. Grigoris Balakian witnessed the genocide from many angles and swore to document it if he survived. According to his great-nephew, Grigoris Balakian at times "lived like an animal" in order to do so.

With the approach of Armenian Remembrance Day, a commemoration held worldwide on April 24, Americans would be well-advised to read this memoir, which recognizes the Ottoman Empire's targeted killing of its Armenian citizens from 1915 to 1918 as genocide. Turkish soldiers, government-organized death squads and ordinary Turks, acting under orders and incitements from Ottoman Minister of the Interior Mehmet Talaat, massacred -- indeed, sometimes literally hacked to pieces -- up to 1.5 million Armenians.

Over nine decades, many wriers have tried to bring attention to what happened in Ottoman Anatolia between 1915 and 1918. Studies of the topic have included Peter Balakian's The Burning Tigris and Black Dog of Fate, Vakahn Dadrian's The History of the Armenian Genocide, the great historian Merrill Peterson's Starving Armenians, and Michael Bobelian's Children of Armenia. Most important of all is Turkish historian Taner Akcam's courageous A Shameful Act, a book that no less than Nobel Laureate Orhan Pamuk, defying legal threats, called "the definitive account of the organized destruction of the Ottoman Armenians."

From the moment Turkish forces arrested Father Balakian, a vartabed or celibate priest, along with approximately 250 other Armenian intellectuals in Constantinople on April 24, 1915, he disciplined himself over four years of forced marches, occasional starvation, infestation by lice and multiple last-minute escapes, to record what he was seeing and hearing, to articulate it to himself even when he lacked pen or paper, so that he could report the atrocities later.

This book thus honors the commitment made by Father Balakian to a number of fellow deportees who eventually died. They implored him: Write about this if you live. Tell people what happened. Over hundreds of pages we witness, through Balakian's eyes, Turkish police and soldiers deport and later, with the help of ordinary villagers and chetes (killing squads of prisoners released precisely to kill Armenians), ferociously behead, disembowl and mutilate countless Armenians with hatchets, axes, cleavers, knives, shovels and pitchforks as the prisoners trudge eastward on forced marches, at times accompanying the mayhem with shouts of "Allah! Allah!"

That savagery came on top of the rape of many young Armenian women, and at times their forced conversion to Islam, as well as expropriation of almost all Armenian property and wealth. Some scenes in Armenian Golgotha are unbearable. A small group that includes an American teacher and two Germans comes across a field WITH "pools of blood." It contains hundreds of naked Armenian corpses, most "with their heads and limbs cut off," and their entrails spilled out.

One of the Germans, a nurse, "jumped from her horse and ran to hug the decapitated body of a six-month-old girl. She kissed the baby and wailed, saying she wanted to take her, that she was her daughter."

Unable to stop the nurse, "who had gone mad," as she lept from one dismembered child's body to another, hugging and kissing them, the others had to forcibly restrain her. She was "tied to her horse" and eventually placed in a German hospital.

What she'd seen, Grigoris Balakian explains, wasn't unusual. After a massacre, Turkish village women would slit open Armenian corpses, especially the intestines, seeking swallowed jewelry. (They found a fair amount of it.) Sometimes, he writes, Armenian women abandoned their emaciated infants on death piles, still alive, deeming it a better death than being hacked to pieces. One witness reported that she saw starving Armenian "mothers gone mad who had thrown their newly deceased little children into the fire" and then eaten them, "half cooked or half raw."

Alongside such grisly tales, Grigor Balakian provides background, woven into his personal narrative, on Ottoman history. He analyzes with great subtlety not only the geopolitical assumptions and strategies of all groups involved, but also the psychology of individual players, including Talaat and his "goal of annihilating the Armenian race."

With its long overdue publication in English, Armenian Golgotha joins Primo Levi's Survival in Auschwitz and other stellar works on the Holocaust as a classic of genocide literature. Just as Levi's classic guarantees that any reader who finishes it will shudder at questioning of the Holocaust, those who make it through Armenian Golgotha should feel moral fury at Turkey for how it has, over almost nine decades, denied and falsified its predecessor's massive crimes against its own citizens, never apologized for them, and never paid a lira of reparations.

Read Grigoris Balakian and weep.

Carlin Romano, Critic-at-Large of The Chronicle of Higher Education, teaches media theory and philosophy at the University of Pennsylvania.

Copyright © 2010, Chicago Tribune

For more on the Armanian Genocide visit our web page

Copies available for loan at CHGS

Chigago Tribune Book Review

Carlin Romano

Special to the Tribune

"Armenian Golgotha: A Memoir of the Armenian Genocide, 1915-18"

By Grigoris Balakian

Translated by Peter Balakian with Aris Sevag

Alfred A. Knopf. 509 pp. $35

Armenian Golgotha is the astonishing memoir of Father Grigoris Balakian (1876-1934), a work from the 1920s shepherded into English by his great nephew Peter Balakian, the leading American expert on the ARMENIAN genocide. Grigoris Balakian witnessed the genocide from many angles and swore to document it if he survived. According to his great-nephew, Grigoris Balakian at times "lived like an animal" in order to do so.

With the approach of Armenian Remembrance Day, a commemoration held worldwide on April 24, Americans would be well-advised to read this memoir, which recognizes the Ottoman Empire's targeted killing of its Armenian citizens from 1915 to 1918 as genocide. Turkish soldiers, government-organized death squads and ordinary Turks, acting under orders and incitements from Ottoman Minister of the Interior Mehmet Talaat, massacred -- indeed, sometimes literally hacked to pieces -- up to 1.5 million Armenians.

Over nine decades, many wriers have tried to bring attention to what happened in Ottoman Anatolia between 1915 and 1918. Studies of the topic have included Peter Balakian's The Burning Tigris and Black Dog of Fate, Vakahn Dadrian's The History of the Armenian Genocide, the great historian Merrill Peterson's Starving Armenians, and Michael Bobelian's Children of Armenia. Most important of all is Turkish historian Taner Akcam's courageous A Shameful Act, a book that no less than Nobel Laureate Orhan Pamuk, defying legal threats, called "the definitive account of the organized destruction of the Ottoman Armenians."

From the moment Turkish forces arrested Father Balakian, a vartabed or celibate priest, along with approximately 250 other Armenian intellectuals in Constantinople on April 24, 1915, he disciplined himself over four years of forced marches, occasional starvation, infestation by lice and multiple last-minute escapes, to record what he was seeing and hearing, to articulate it to himself even when he lacked pen or paper, so that he could report the atrocities later.

This book thus honors the commitment made by Father Balakian to a number of fellow deportees who eventually died. They implored him: Write about this if you live. Tell people what happened. Over hundreds of pages we witness, through Balakian's eyes, Turkish police and soldiers deport and later, with the help of ordinary villagers and chetes (killing squads of prisoners released precisely to kill Armenians), ferociously behead, disembowl and mutilate countless Armenians with hatchets, axes, cleavers, knives, shovels and pitchforks as the prisoners trudge eastward on forced marches, at times accompanying the mayhem with shouts of "Allah! Allah!"

That savagery came on top of the rape of many young Armenian women, and at times their forced conversion to Islam, as well as expropriation of almost all Armenian property and wealth. Some scenes in Armenian Golgotha are unbearable. A small group that includes an American teacher and two Germans comes across a field WITH "pools of blood." It contains hundreds of naked Armenian corpses, most "with their heads and limbs cut off," and their entrails spilled out.

One of the Germans, a nurse, "jumped from her horse and ran to hug the decapitated body of a six-month-old girl. She kissed the baby and wailed, saying she wanted to take her, that she was her daughter."

Unable to stop the nurse, "who had gone mad," as she lept from one dismembered child's body to another, hugging and kissing them, the others had to forcibly restrain her. She was "tied to her horse" and eventually placed in a German hospital.

What she'd seen, Grigoris Balakian explains, wasn't unusual. After a massacre, Turkish village women would slit open Armenian corpses, especially the intestines, seeking swallowed jewelry. (They found a fair amount of it.) Sometimes, he writes, Armenian women abandoned their emaciated infants on death piles, still alive, deeming it a better death than being hacked to pieces. One witness reported that she saw starving Armenian "mothers gone mad who had thrown their newly deceased little children into the fire" and then eaten them, "half cooked or half raw."

Alongside such grisly tales, Grigor Balakian provides background, woven into his personal narrative, on Ottoman history. He analyzes with great subtlety not only the geopolitical assumptions and strategies of all groups involved, but also the psychology of individual players, including Talaat and his "goal of annihilating the Armenian race."

With its long overdue publication in English, Armenian Golgotha joins Primo Levi's Survival in Auschwitz and other stellar works on the Holocaust as a classic of genocide literature. Just as Levi's classic guarantees that any reader who finishes it will shudder at questioning of the Holocaust, those who make it through Armenian Golgotha should feel moral fury at Turkey for how it has, over almost nine decades, denied and falsified its predecessor's massive crimes against its own citizens, never apologized for them, and never paid a lira of reparations.

Read Grigoris Balakian and weep.

Carlin Romano, Critic-at-Large of The Chronicle of Higher Education, teaches media theory and philosophy at the University of Pennsylvania.

Copyright © 2010, Chicago Tribune

For more on the Armanian Genocide visit our web page

Labels:

"Peter Balakian",

Armenia,

Breaking News on the Web,

genocide

Friday, October 22, 2010

New Online Resource Debuts For Nazi-Era Looted Art

National Public Radio

by THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

NEW YORK October 18, 2010, 08:41 am ET

The Nazis stripped hundreds of thousands of artworks from Jews during World War II in one of the biggest cultural raids in history, often photographing their spoils and meticulously cataloguing them on typewritten index cards.

Holocaust survivors and their relatives, as well as art collectors and museums, can go online beginning Monday to search a free historical database of more than 20,000 art objects stolen in Germany-occupied France and Belgium from 1940 to 1944, including paintings by Claude Monet and Marc Chagall.

The database is a joint project of the New York-based Conference of Jewish Material Claims Against Germany and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.

The database is unusual because it has been built around Nazi-era records that were digitized and rendered searchable, showing what was seized and from whom, along with data on restitution or repatriation and photographs taken of the seized objects, the groups told The Associated Press.

The Claims Conference, which helps Holocaust survivors and their relatives to reclaim property, said it had used the database to estimate that nearly half of the objects may never have been returned to their rightful owners or their descendants or their country of origin.

"Most people think or thought that most of these items were repatriated or restituted," said Wesley A. Fisher, director of research at the Claims Conference. "It isn't true. Over half of them were never repatriated. That in itself is rather interesting historically."

Marc Masurovsky, the project's director at the museum, said the database was designed to evolve as new information is gathered. "I hope that the families do consult it and tell us what is right and what is wrong with it," he added.

The database combines records from the U.S. National Archives in College Park, Md.; the German Bundesarchiv, the federal archive in Koblenz; and repatriation and restitution records held by the French government.

By giving a new view of looted art, the database could raise questions about the possibly tainted history of works of art in some of the world's most important museum collections, experts said.

"I always tell people we have no idea how much is out there because nobody has ever bothered to take a complete inventory," said Willi Korte, one of the most prominent independent provenance researchers of looted Nazi art. "I think all of those that say there's not much left to do certainly should think twice."

Korte has been at the forefront of the worldwide search for art looted by the Nazis, an undertaking that has accelerated over the past two decades, spurring court battles and pitting the descendants of Jewish families who were forced to give up their possession against museums and private collectors.

Among the works listed in the database is a painting by the Danish artist Philips Wouwerman, which had belonged to the Rothschilds family and was discovered in the secret Zurich vault of Reich art dealer Bruno Lohse in 2007.

Korte, who was asked to develop an inventory of the works in the Lohse vault, said the Wouwerman painting "was clearly plundered."

No one knows exactly how many objects the Nazis looted and how many may still be missing.

The Claims Conference says about 650,000 art objects were taken, and thousands of items are still lost.

But the true number may never be known because of lack of documentation, the passage of time and the absence of a central arbitration body.

Some museum organizations have argued in recent years that most looted art has been identified as researchers focus on the provenance of art objects.

The database includes only a slice of the records generated by the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg, an undertaking of Third Reich ideologue Alfred Rosenberg to seize archives, books, art, Judaica, home furnishings and other objects from Jewish families, bookstores and collections. Records of the looting were disbursed to nearly a dozen countries after the war.

The database is focused on ERR spoils shipped to a prewar museum near the Louvre, where they were often catalogued and sold back to the market, destroyed or integrated into the lavish private collections of top Nazi officials -- including the military chief Hermann Goering.

Julius Berman, the chairman of the Claims Conference, said organizing Nazi art-looting records was a key step to righting an injustice.

"It is now the responsibility of museums, art dealers and auction houses to check their holdings against these records to determine whether they might be in possession of art stolen from Holocaust victims," he said.

To view the database visit the ERR Project website.

The link will also be available on CHGS website on our web links page.

Educators we have copies of the book and DVD Rape of Europa

Study guide is also available for download or view in PDF. The_Rape_of_Europa_study_guide.pdf

by THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

NEW YORK October 18, 2010, 08:41 am ET

The Nazis stripped hundreds of thousands of artworks from Jews during World War II in one of the biggest cultural raids in history, often photographing their spoils and meticulously cataloguing them on typewritten index cards.

Holocaust survivors and their relatives, as well as art collectors and museums, can go online beginning Monday to search a free historical database of more than 20,000 art objects stolen in Germany-occupied France and Belgium from 1940 to 1944, including paintings by Claude Monet and Marc Chagall.

The database is a joint project of the New York-based Conference of Jewish Material Claims Against Germany and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.

The database is unusual because it has been built around Nazi-era records that were digitized and rendered searchable, showing what was seized and from whom, along with data on restitution or repatriation and photographs taken of the seized objects, the groups told The Associated Press.

The Claims Conference, which helps Holocaust survivors and their relatives to reclaim property, said it had used the database to estimate that nearly half of the objects may never have been returned to their rightful owners or their descendants or their country of origin.

"Most people think or thought that most of these items were repatriated or restituted," said Wesley A. Fisher, director of research at the Claims Conference. "It isn't true. Over half of them were never repatriated. That in itself is rather interesting historically."

Marc Masurovsky, the project's director at the museum, said the database was designed to evolve as new information is gathered. "I hope that the families do consult it and tell us what is right and what is wrong with it," he added.

The database combines records from the U.S. National Archives in College Park, Md.; the German Bundesarchiv, the federal archive in Koblenz; and repatriation and restitution records held by the French government.

By giving a new view of looted art, the database could raise questions about the possibly tainted history of works of art in some of the world's most important museum collections, experts said.

"I always tell people we have no idea how much is out there because nobody has ever bothered to take a complete inventory," said Willi Korte, one of the most prominent independent provenance researchers of looted Nazi art. "I think all of those that say there's not much left to do certainly should think twice."

Korte has been at the forefront of the worldwide search for art looted by the Nazis, an undertaking that has accelerated over the past two decades, spurring court battles and pitting the descendants of Jewish families who were forced to give up their possession against museums and private collectors.

Among the works listed in the database is a painting by the Danish artist Philips Wouwerman, which had belonged to the Rothschilds family and was discovered in the secret Zurich vault of Reich art dealer Bruno Lohse in 2007.

Korte, who was asked to develop an inventory of the works in the Lohse vault, said the Wouwerman painting "was clearly plundered."

No one knows exactly how many objects the Nazis looted and how many may still be missing.

The Claims Conference says about 650,000 art objects were taken, and thousands of items are still lost.

But the true number may never be known because of lack of documentation, the passage of time and the absence of a central arbitration body.

Some museum organizations have argued in recent years that most looted art has been identified as researchers focus on the provenance of art objects.

The database includes only a slice of the records generated by the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg, an undertaking of Third Reich ideologue Alfred Rosenberg to seize archives, books, art, Judaica, home furnishings and other objects from Jewish families, bookstores and collections. Records of the looting were disbursed to nearly a dozen countries after the war.

The database is focused on ERR spoils shipped to a prewar museum near the Louvre, where they were often catalogued and sold back to the market, destroyed or integrated into the lavish private collections of top Nazi officials -- including the military chief Hermann Goering.

Julius Berman, the chairman of the Claims Conference, said organizing Nazi art-looting records was a key step to righting an injustice.

"It is now the responsibility of museums, art dealers and auction houses to check their holdings against these records to determine whether they might be in possession of art stolen from Holocaust victims," he said.

To view the database visit the ERR Project website.

The link will also be available on CHGS website on our web links page.

Educators we have copies of the book and DVD Rape of Europa

Study guide is also available for download or view in PDF. The_Rape_of_Europa_study_guide.pdf

Labels:

"Looted art",

Breaking News on the Web,

Holocaust,

Nazis,

Restitution,

WWII

Tuesday, October 19, 2010

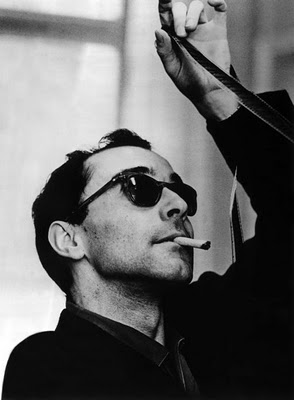

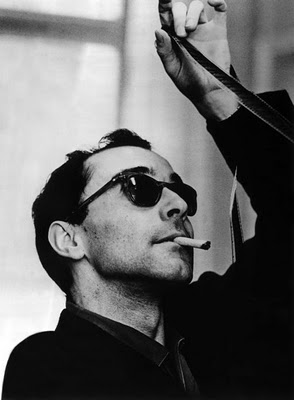

Jean-Luc Godard, anti-Semite?

Bruno Chaouat, director

It was recently announced by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences that Jean-Luc Godard, the Swiss-French filmmaker, will receive an honorary Oscar at this year's ceremony (see article from Jewish Journal posted by CHGS on October 16th, 2010). With this announcement came articles, blog posts and op-eds referring to the filmmaker's real or alleged anti-Semitism.

It is important for the world of scholarship to connect with current events, and we post these articles in order to examine these events with a sense of nuance and depth that the complexity of culture and history requires. While journalism often makes the complexity of the world accessible at the cost of simplifying it, the mission of an academic center such as ours is to approach this complexity with rigor, scientific and intellectual integrity and without sensationalizing.

It is particularly timely that Professor Philip Watts from Columbia University will speak in April about Godard, WWII, the Jews and the Holocaust at CHGS's lecture series, "Alternative Narratives or Denial?" Professor Watts will examine portions of Godard's work and discuss how his history may have shaped and informed his cinematographic choices which have led to the anti-Semitic charges.

We look forward to this exchange, and will continue to look at current events and provide a platform to lead us into deeper inquiry beyond the headlines.

It was recently announced by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences that Jean-Luc Godard, the Swiss-French filmmaker, will receive an honorary Oscar at this year's ceremony (see article from Jewish Journal posted by CHGS on October 16th, 2010). With this announcement came articles, blog posts and op-eds referring to the filmmaker's real or alleged anti-Semitism.

It is important for the world of scholarship to connect with current events, and we post these articles in order to examine these events with a sense of nuance and depth that the complexity of culture and history requires. While journalism often makes the complexity of the world accessible at the cost of simplifying it, the mission of an academic center such as ours is to approach this complexity with rigor, scientific and intellectual integrity and without sensationalizing.

It is particularly timely that Professor Philip Watts from Columbia University will speak in April about Godard, WWII, the Jews and the Holocaust at CHGS's lecture series, "Alternative Narratives or Denial?" Professor Watts will examine portions of Godard's work and discuss how his history may have shaped and informed his cinematographic choices which have led to the anti-Semitic charges.

We look forward to this exchange, and will continue to look at current events and provide a platform to lead us into deeper inquiry beyond the headlines.

Labels:

anti-Semitism,

CHGS,

Godard,

homepage,

Watts

Friday, October 15, 2010

German Jewish leader welcomes Hitler exhibition

(AP) - 5 hours ago

BERLIN (AP) -- A German Jewish leader welcomed a new exhibition in Berlin exploring the Adolf Hitler personality cult that helped the Nazis win and hold power, saying Friday that it takes a good approach to a difficult issue.

"Hitler and the Germans -- Nation and Crime," which runs through Feb. 6 at the German Historical Museum, is the first exhibition in the capital to focus so firmly on Hitler's role -- another step in the erosion of taboos concerning depictions of the Nazi era.

"I think it's a good exhibition -- it is a serious approach to the theme, which is without doubt difficult to deal with," Stephan Kramer, the general secretary of the Central Council of Jews, told AP Television News as the show opened to the public.

The exhibition portrays the Nazis' dual approach of making the German masses feel included in their movement while excluding those who they had identified as enemies, such as Jews, Gypsies, gays and the disabled. It illustrates the German masses' willingness to support those policies.

It juxtaposes items such as busts of Hitler and Nazi-era toys with artifacts from concentration camps and footage of events such as the book-burning that followed Hitler's rise to power.

The exhibition "is happening at the right time," Kramer said.

He pointed to a recent debate over a book claiming German society was being made "dumber" by Muslim immigrants as evidence of how, even now, "the lower middle class can be seduced ... (and) its fears pandered to."

The book, written by a former board member of Germany's central bank, has become a best-seller and reignited a debate about the difficulties of integrating immigrants.

Kramer said he worried that the people who might have most to learn from the Hitler exhibition wouldn't go to see it, "but that remains to be seen."

Jetin Habstaat, a tourist from Oslo, Norway, said that the show offers "a brilliant exhibition of contrasts."

"One can see the propaganda but also the opposition," he said.

Copyright © 2010 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

BERLIN (AP) -- A German Jewish leader welcomed a new exhibition in Berlin exploring the Adolf Hitler personality cult that helped the Nazis win and hold power, saying Friday that it takes a good approach to a difficult issue.

"Hitler and the Germans -- Nation and Crime," which runs through Feb. 6 at the German Historical Museum, is the first exhibition in the capital to focus so firmly on Hitler's role -- another step in the erosion of taboos concerning depictions of the Nazi era.

"I think it's a good exhibition -- it is a serious approach to the theme, which is without doubt difficult to deal with," Stephan Kramer, the general secretary of the Central Council of Jews, told AP Television News as the show opened to the public.

The exhibition portrays the Nazis' dual approach of making the German masses feel included in their movement while excluding those who they had identified as enemies, such as Jews, Gypsies, gays and the disabled. It illustrates the German masses' willingness to support those policies.

It juxtaposes items such as busts of Hitler and Nazi-era toys with artifacts from concentration camps and footage of events such as the book-burning that followed Hitler's rise to power.

The exhibition "is happening at the right time," Kramer said.

He pointed to a recent debate over a book claiming German society was being made "dumber" by Muslim immigrants as evidence of how, even now, "the lower middle class can be seduced ... (and) its fears pandered to."

The book, written by a former board member of Germany's central bank, has become a best-seller and reignited a debate about the difficulties of integrating immigrants.

Kramer said he worried that the people who might have most to learn from the Hitler exhibition wouldn't go to see it, "but that remains to be seen."

Jetin Habstaat, a tourist from Oslo, Norway, said that the show offers "a brilliant exhibition of contrasts."

"One can see the propaganda but also the opposition," he said.

Copyright © 2010 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

Labels:

Art,

Breaking News on the Web,

Hitler,

Jewish,

Nazis

Wednesday, October 13, 2010

Rwanda: The Country Welcomes War Crimes Suspect's Arrest

by Alexandra Brangeon

13 October 2010

Allafrica.com

Rwanda has welcomed France's arrest of rebel leader Callixte Mbarushimana who is charged with war crimes and crimes against humanity in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Rwanda's Justice Minister Tharcisse Karugarama told RFI on Wednesday that it was a "step in the right direction". Survivors of the genocide said that this should not mean that his role in Rwandan genocide should be forgotten.

"We would have wished that he had been arrested under the warrant of arrest issued by the Rwandan government to face charges of genocide committed in Rwanda in 1994. This has not happened," says Karugarama.

"The French judicial authorities have arrested Callixte Mbarushimana under the basis of a warrant of arrest issued by the ICC [International Criminal Court]," which refer to alleged crimes committed in the Kivus, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Karugarama says this was not Rwanda's preferred option although he ruled out requesting an extradition order following his arrest.

Q&A - Rwanda's Justice Minister Tharcisse Karugarama

As long as there is some form of justice going on, I think we have to live with that

"I think once one process is going on it is important to give that process time to take its course and make appropriate decisions."

Survivors of the 1994 genocide have welcomed Mbarushimana's arrest, but said his part in the massacre should not be forgotten.

"His arrest in itself is good news, but it shouldn't mask his role in the genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda in 1994," Theodore Simburudali, the head of Ibuka, the genocide survivors' association, told the AFP news agency.

The United States also hailed Mbarushimana's arrest. State Department spokesperson Philip Crowley said it "sends an important signal".

"The international community will not tolerate the FDLR's [Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda] continuing efforts to destabilize the eastern provinces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo," Crowley said in a statement.

Mbarushimana, who is a former United Nations employee, was arrested in Paris on Monday and faces five charges of crimes against humanity and six war crime charges for murders, rapes, torture and destruction of property in eastern DRC in 2009.

He is not on the list of genocide suspects sought by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda.

Labels:

Breaking News on the Web,

Genocide,

Rwanda

Monday, October 11, 2010

The Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies at the University of Minnesota presents the groundbreaking documentary Einsatzgruppen: The Death Brigades

Thursday, November 4 at 7:00p.m.

Sunday, November 7 at 6:30p.m.

Followed by a question and answer session with filmmaker Michael Prazan

Moderated by Rembert Hueser

Department of German, Scandinavian & Dutch Studies

and Moving Image Studies

St. Anthony Main Theater

115 Main St SE

Minneapolis

Tickets: $6.00 students /senior $8.50 general admission

Michael Prazan's documentary details the SS killing squads charged with destroying entire Jewish populations in occupied Eastern Europe during World War II. Referred to as the "Holocaust by Bullets," the mobile death units moved through Eastern Europe into Soviet territories in 1941, recruiting assistants in the Baltics and the Ukraine to help them carry out the extermination of the Jews in towns, cities and villages. The brigades were only a prelude to the mass exterminations that followed at the death camps in Poland.

The film contains previously unseen archival footage, much of it in color, some shot as home movies by the Germans themselves. Prazan interviews historians, Holocaust survivors, witnesses, and perpetrators to give a complete view of the horror and scale of this operation which was responsible for the deaths of millions of innocent Jewish families.

French filmmaker Michael Prazan lived in Japan for several years while making his first two films The Nanking Massacre: Memory and Oblivion (2006) and Japan, the Red Years (2002), about the terrorist tendencies of some of Japan's May '68 children. He has written a book on the making of the Einsatzgruppen film, which will be published in France later this year.

Co-sponsors: Minnesota Film Arts, University of Minnesota Department of History, Department of French and Italian, Department of German, Scandinavian & Dutch Studies, Moving Image Studies, Center for Jewish Studies and the Human Rights Center at the School of Law.

To read a review of the film click here.

For information on Einsatzgruppen click here

Labels:

Breaking News on the Web,

Einsatzgruppen,

film,

Holocaust,

homepage,

Prazan

Is Jean-Luc Godard an anti-Semite?

CHGS will explore this question more in depth during our lecture series "Alternative Narratives or Denial?" in March and April of 2011. check our web site for updates and information coming soon.

October 6, 2010

Is Jean-Luc Godard an anti-Semite?

Jean-Luc Godard to get honorary Oscar, questions of anti-Semitism remain

By Tom Tugend

JewishJournal.com

Hollywood's Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences has announced that it will bestow an honorary Oscar on iconic Swiss-French filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard on Nov. 13.The announcement has raised a new question and revived an old one. First, will Godard show up to accept the award? Second, is he an anti-Semite?

Both questions can be answered with a categorical "maybe yes or maybe no." Godard, who will mark his 80th birthday in December, is one of the originators, and among the last survivors, of the French New Wave cinema, which he helped kick-start in 1960 with "Breathless," still his best-known work.

He and his cohorts, among them Francois Truffaut and Eric Rohmer, rebelled against the traditional French movie, and later against all things Hollywood.

The New Wave elevated the role of the director as the sole auteur of a movie and viewed film as a fluid audiovisual language, freed of the constraints of formal story lines, plot, narration and sequence.

As Godard put it, "I believe a film should have a beginning, a middle and an end, but not necessarily in that order."

To a small coterie of cinephiles and most professional film critics, especially in Europe, Godard is considered the ultimate cinematic genius. To others, his films often seem insufferably opaque and incomprehensible.

In the 50 years since his film debut, Godard has proven his vigor and inventiveness in 70 features and is credited with strongly influencing such American directors as Martin Scorsese, Quentin Tarantino and Steven Soderbergh.

Godard's long career has been marked by constant artistic disputes and charges of anti-Semitism and anti-Zionism, as noted in three biographies: "Godard: A Portrait of the Artist at 70" (2003) by American professor Colin MacCabe; "Everything Is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard" (2008) by Richard Brody, an editor and writer for the New Yorker; and "Godard" by film historian Antoine de Baecque.

The last was published in March in French and is not easily available. Material used in this article was drawn from reviews and analyses of the book.

The early seeds of Godard's alleged anti-Semitism and acknowledged anti-Zionism may have been planted in the home of his affluent Swiss-French Protestant family.

In a 1978 lecture in Montreal, he spoke of his family's own political history as World War II "collaborators" who rooted for a German victory, and of his grandfather as "ferociously not even anti-Zionist, but he was anti-Jew; whereas I am anti-Zionist, he was anti-Semitic."

Godard validated his anti-Israel credentials in 1970 by filming "Until Victory," depicting the "Palestinian struggle for independence," partially bankrolled by the Arab League.

The project was eventually aborted, but Godard used some of the footage in his 1976 documentary, "Ici et ailleurs" ("Here and Elsewhere"), contrasting the lives of two families -- one French and one Palestinian.

In it, Godard inserted alternating blinking images of Golda Meir and Adolf Hitler, and suggested, in reference to the 1972 Munich Olympics massacre, that "before every Olympic finale, an image of a Palestinian [refugee] camp should be broadcast."

Biographer Brody, like the other authors, is an ardent admirer of Godard the artist, but he notes that in the filmmaker's later work, "Godard's obsession with living history ... has brought with it a troubling set of idées fixes, notably regarding Jews and the United States."

Godard has been able to combine both targets in his attacks on Hollywood, and, of course, the Jews who run it.

He has always been obsessed by the Holocaust, and after the 1993 release of "Schindler's List," the film and its director, Steven Spielberg, became Godard's favorite whipping boys. As in many of his attacks on Hollywood, it is at times difficult to discern whether Godard's hostility is based on artistic differences or anti-Semitism, or a bit of each.

The leitmotif running through Godard's own work is the superiority of "images" as against "texts" or narratives, or, as he puts it, "the great conflict between the seen and the said."

He faults, for instance, Claude Lanzmann's monumental nine-hour film, "Shoah," for its use of personal narratives by survivors and others, and proposes that the Holocaust can only be truly represented by showing the home life of one of the concentration camp guards.

Who is to blame for the Jewish preference of text over image? It is Moses, Godard's "greatest enemy," who "saw the bush in flames and who came down from the mountain and didn't say, 'This is what I saw,' but, 'Here are the tablets of the law.' "

For the untutored layman, unfamiliar with the methods and passions of movie making, this and other Godard pronouncements can take on an Alice-in-Wonderland quality.

A key may be found in a recent London Sunday Times story, in which a reporter interviewed one of Godard's oldest friends, a retired geology professor.

"He [Godard] is on a different level from the rest of us, somewhere between genius and completely round the bend," the professor explained.

Artistic differences aside, there are disturbing instances of Godard's anti-Semitism, particularly directed against some of his closest collaborators. According to the three biographers, at one point Godard called producer Pierre Braunberger, an early supporter of the New Wave filmmakers, a "sale Juif " (filthy Jew).

In another case, when longtime collaborator Jean-Pierre Gorin requested some back pay, Godard noted, "Ah, it's always the same, Jews call you when they hear a cash register opening."

When this reporter submitted some of Godard's anti-Semitic utterances to the Motion Picture Academy and requested comments, the request prompted the following written response:

"The Academy is aware that Jean-Luc Godard has made statements in the past that some have construed as anti-Semitic. We are also aware of detailed rebuttals to that charge. Anti-Semitism is of course deplorable, but the Academy has not found the accusations against M. Godard persuasive.

"The Academy's Honorary Awards are presented in recognition of an individual's extraordinary contributions to the art of the motion picture. The organization intends to bestow an honorary Oscar on M. Godard at its second annual Governors Awards on November 13th."

After a follow-up request as to the source of the "detailed rebuttals," an Academy spokeswoman cited a 2009 article in the Canadian magazine Cinema Scope by Bill Krohn, Hollywood correspondent for the influential French film magazine Cahiers du Cinema, to which Godard and many of the early New Wave directors contributed as film critics.

Krohn took on Brody's biography and accused its author of ideological simplification, biographical reductivism, guilt by association, misinterpretations, hurt self-esteem following a snub by Godard and, all in all, of perpetrating "a hatchet job disguised as a celebration of Godard's genius."

Krohn's critique is quite diffuse and short on specifics, but in one concrete instance he illustrates that the same words can be interpreted in different ways.

Although Godard's exclamation of "filthy Jew" was taken by Braunberger as a deadly insult, Krohn interprets it as affectionate banter between old friends and an allusion to the film "La grande illusion."

Perhaps a better defense of Godard may be found in some of the filmmaker's own projects and views, however erratic they may appear.

Given his family background and pro-Palestinian activism, it would not be surprising if Godard were also a Holocaust denier.

But, on the contrary, he is fixated on the murder of6 million, including some 77,000 Jews living in France, and one of his main charges against Hollywood is that Jewish studio heads could have prevented the Shoah by producing a number of anti-Nazi films in the 1930s.

He has labeled repeated accusations that some of his films equate the Palestinian Nakba (defeat in the 1948-49 war) with the Holocaust as "completely idiotic."

In some of Godard's enigmatic films, the same movie may contain both negative and positive themes. For instance, in his 2001 picture "Éloge de l'amour" (In Praise of Love), Godard attacks Spielberg in particular, and America in general, for its perceived lack of history and culture.

He also inserts the last testament of a notorious French fascist and anti-Semite, but on the other hand, the movie also deals with the quest to restore Nazi-looted art to the rightful Jewish and other owners.

Earlier this year, it was reported that Godard was preparing an adaptation of Daniel Mendelsohn's "The Lost: A Search for Six of Six Million," with Israeli filmmaker Oren Moverman.

In an attempt to get additional input on Godard's character and reputation, this reporter contacted several entertainment industry personalities in Hollywood and abroad.

One was Arthur Cohn, the Swiss film producer and winner of six Oscars, including one for the classic "The Garden of the Finzi-Continis," and an ardent Zionist and Jewish activist. Others were Rabbi Marvin Hier, head of the Simon Wiesenthal Center and multiple Academy Award winner; noted UCLA film historian Howard Suber; and writer-producer Lionel Chetwynd.

In one form or another, each said that he had no personal knowledge of Godard's reputed anti-Semitism.

Spielberg is shooting a film in Europe and was not available for comment. However, Marvin Levy, Spielberg's personal spokesman, responded to a query on how Spielberg had dealt with Godard's personal attacks on him and his films, particularly "Schindler's List."

"I don't recall anything from Steven at that time or through the years," Levy responded. "He may have known about Godard's thoughts on 'Schindler's List,' but I never heard him talk about it. All the acclaim overwhelmed any negatives from anybody. It would have been uncharacteristic of him to get into a confrontation with another filmmaker who didn't like his film."

Attempts to reach Godard through the head of his Swiss production company were unsuccessful. This failure will not surprise anyone who has followed the comedic drama of trying to pin down whether Godard will actually attend the Academy's Governors Awards dinner in November at the Hollywood & Highland Center.

At the same event, producer-director Francis Ford Coppola will receive the Irving G. Thalberg Memorial Award, and, in addition to Godard, actor Eli Wallach and historian-preservationist Kevin Brownlow have been chosen for honorary Oscars.

Despite a flurry of faxes, e-mails and couriered letters, Godard did not respond to the invitation for weeks, until some enterprising British reporters tracked him at his home in the Swiss town of Rolle.

Godard escaped the reporters, but Anne-Marie Mieville, his wife and work partner, said Godard was apparently disappointed that the honor would not be conferred at the main Oscars ceremony next February.

In any case, she said, Godard "is getting too old for this kind of thing. Would you go all that way just for a bit of metal?"

The French newspaper Liberation commented that it might be just as well if Godard stayed home, as his speeches "have become mysterious adventures in the country of language."

Nevertheless, the Academy remains officially upbeat, though hedging its bets by stating carefully that it "intends to bestow an honorary Oscar on M. Godard."

Though he may not like to travel, Godard continues to make new films with considerable vigor. His latest, "Socialism," screened at the New York Film Festival on Sept. 29 and will be shown again on Oct. 8.

Benjamin Ivry, a frequent contributor to the Forward, contributed to this article.

© Copyright 2010 Tribe Media Corp.

All rights reserved. JewishJournal.com is hosted by Nexcess.net. Homepage design by Koret Communications.

Widgets by Mijits. Site construction by Hop Studios

October 6, 2010

Is Jean-Luc Godard an anti-Semite?

Jean-Luc Godard to get honorary Oscar, questions of anti-Semitism remain

By Tom Tugend

JewishJournal.com

Hollywood's Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences has announced that it will bestow an honorary Oscar on iconic Swiss-French filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard on Nov. 13.The announcement has raised a new question and revived an old one. First, will Godard show up to accept the award? Second, is he an anti-Semite?

Both questions can be answered with a categorical "maybe yes or maybe no." Godard, who will mark his 80th birthday in December, is one of the originators, and among the last survivors, of the French New Wave cinema, which he helped kick-start in 1960 with "Breathless," still his best-known work.

He and his cohorts, among them Francois Truffaut and Eric Rohmer, rebelled against the traditional French movie, and later against all things Hollywood.

The New Wave elevated the role of the director as the sole auteur of a movie and viewed film as a fluid audiovisual language, freed of the constraints of formal story lines, plot, narration and sequence.

As Godard put it, "I believe a film should have a beginning, a middle and an end, but not necessarily in that order."

To a small coterie of cinephiles and most professional film critics, especially in Europe, Godard is considered the ultimate cinematic genius. To others, his films often seem insufferably opaque and incomprehensible.

In the 50 years since his film debut, Godard has proven his vigor and inventiveness in 70 features and is credited with strongly influencing such American directors as Martin Scorsese, Quentin Tarantino and Steven Soderbergh.

Godard's long career has been marked by constant artistic disputes and charges of anti-Semitism and anti-Zionism, as noted in three biographies: "Godard: A Portrait of the Artist at 70" (2003) by American professor Colin MacCabe; "Everything Is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard" (2008) by Richard Brody, an editor and writer for the New Yorker; and "Godard" by film historian Antoine de Baecque.

The last was published in March in French and is not easily available. Material used in this article was drawn from reviews and analyses of the book.

The early seeds of Godard's alleged anti-Semitism and acknowledged anti-Zionism may have been planted in the home of his affluent Swiss-French Protestant family.

In a 1978 lecture in Montreal, he spoke of his family's own political history as World War II "collaborators" who rooted for a German victory, and of his grandfather as "ferociously not even anti-Zionist, but he was anti-Jew; whereas I am anti-Zionist, he was anti-Semitic."

Godard validated his anti-Israel credentials in 1970 by filming "Until Victory," depicting the "Palestinian struggle for independence," partially bankrolled by the Arab League.

The project was eventually aborted, but Godard used some of the footage in his 1976 documentary, "Ici et ailleurs" ("Here and Elsewhere"), contrasting the lives of two families -- one French and one Palestinian.

In it, Godard inserted alternating blinking images of Golda Meir and Adolf Hitler, and suggested, in reference to the 1972 Munich Olympics massacre, that "before every Olympic finale, an image of a Palestinian [refugee] camp should be broadcast."

Biographer Brody, like the other authors, is an ardent admirer of Godard the artist, but he notes that in the filmmaker's later work, "Godard's obsession with living history ... has brought with it a troubling set of idées fixes, notably regarding Jews and the United States."

Godard has been able to combine both targets in his attacks on Hollywood, and, of course, the Jews who run it.

He has always been obsessed by the Holocaust, and after the 1993 release of "Schindler's List," the film and its director, Steven Spielberg, became Godard's favorite whipping boys. As in many of his attacks on Hollywood, it is at times difficult to discern whether Godard's hostility is based on artistic differences or anti-Semitism, or a bit of each.

The leitmotif running through Godard's own work is the superiority of "images" as against "texts" or narratives, or, as he puts it, "the great conflict between the seen and the said."

He faults, for instance, Claude Lanzmann's monumental nine-hour film, "Shoah," for its use of personal narratives by survivors and others, and proposes that the Holocaust can only be truly represented by showing the home life of one of the concentration camp guards.

Who is to blame for the Jewish preference of text over image? It is Moses, Godard's "greatest enemy," who "saw the bush in flames and who came down from the mountain and didn't say, 'This is what I saw,' but, 'Here are the tablets of the law.' "

For the untutored layman, unfamiliar with the methods and passions of movie making, this and other Godard pronouncements can take on an Alice-in-Wonderland quality.

A key may be found in a recent London Sunday Times story, in which a reporter interviewed one of Godard's oldest friends, a retired geology professor.

"He [Godard] is on a different level from the rest of us, somewhere between genius and completely round the bend," the professor explained.

Artistic differences aside, there are disturbing instances of Godard's anti-Semitism, particularly directed against some of his closest collaborators. According to the three biographers, at one point Godard called producer Pierre Braunberger, an early supporter of the New Wave filmmakers, a "sale Juif " (filthy Jew).

In another case, when longtime collaborator Jean-Pierre Gorin requested some back pay, Godard noted, "Ah, it's always the same, Jews call you when they hear a cash register opening."

When this reporter submitted some of Godard's anti-Semitic utterances to the Motion Picture Academy and requested comments, the request prompted the following written response:

"The Academy is aware that Jean-Luc Godard has made statements in the past that some have construed as anti-Semitic. We are also aware of detailed rebuttals to that charge. Anti-Semitism is of course deplorable, but the Academy has not found the accusations against M. Godard persuasive.

"The Academy's Honorary Awards are presented in recognition of an individual's extraordinary contributions to the art of the motion picture. The organization intends to bestow an honorary Oscar on M. Godard at its second annual Governors Awards on November 13th."

After a follow-up request as to the source of the "detailed rebuttals," an Academy spokeswoman cited a 2009 article in the Canadian magazine Cinema Scope by Bill Krohn, Hollywood correspondent for the influential French film magazine Cahiers du Cinema, to which Godard and many of the early New Wave directors contributed as film critics.

Krohn took on Brody's biography and accused its author of ideological simplification, biographical reductivism, guilt by association, misinterpretations, hurt self-esteem following a snub by Godard and, all in all, of perpetrating "a hatchet job disguised as a celebration of Godard's genius."

Krohn's critique is quite diffuse and short on specifics, but in one concrete instance he illustrates that the same words can be interpreted in different ways.

Although Godard's exclamation of "filthy Jew" was taken by Braunberger as a deadly insult, Krohn interprets it as affectionate banter between old friends and an allusion to the film "La grande illusion."

Perhaps a better defense of Godard may be found in some of the filmmaker's own projects and views, however erratic they may appear.

Given his family background and pro-Palestinian activism, it would not be surprising if Godard were also a Holocaust denier.

But, on the contrary, he is fixated on the murder of6 million, including some 77,000 Jews living in France, and one of his main charges against Hollywood is that Jewish studio heads could have prevented the Shoah by producing a number of anti-Nazi films in the 1930s.

He has labeled repeated accusations that some of his films equate the Palestinian Nakba (defeat in the 1948-49 war) with the Holocaust as "completely idiotic."

In some of Godard's enigmatic films, the same movie may contain both negative and positive themes. For instance, in his 2001 picture "Éloge de l'amour" (In Praise of Love), Godard attacks Spielberg in particular, and America in general, for its perceived lack of history and culture.

He also inserts the last testament of a notorious French fascist and anti-Semite, but on the other hand, the movie also deals with the quest to restore Nazi-looted art to the rightful Jewish and other owners.

Earlier this year, it was reported that Godard was preparing an adaptation of Daniel Mendelsohn's "The Lost: A Search for Six of Six Million," with Israeli filmmaker Oren Moverman.

In an attempt to get additional input on Godard's character and reputation, this reporter contacted several entertainment industry personalities in Hollywood and abroad.

One was Arthur Cohn, the Swiss film producer and winner of six Oscars, including one for the classic "The Garden of the Finzi-Continis," and an ardent Zionist and Jewish activist. Others were Rabbi Marvin Hier, head of the Simon Wiesenthal Center and multiple Academy Award winner; noted UCLA film historian Howard Suber; and writer-producer Lionel Chetwynd.

In one form or another, each said that he had no personal knowledge of Godard's reputed anti-Semitism.

Spielberg is shooting a film in Europe and was not available for comment. However, Marvin Levy, Spielberg's personal spokesman, responded to a query on how Spielberg had dealt with Godard's personal attacks on him and his films, particularly "Schindler's List."

"I don't recall anything from Steven at that time or through the years," Levy responded. "He may have known about Godard's thoughts on 'Schindler's List,' but I never heard him talk about it. All the acclaim overwhelmed any negatives from anybody. It would have been uncharacteristic of him to get into a confrontation with another filmmaker who didn't like his film."

Attempts to reach Godard through the head of his Swiss production company were unsuccessful. This failure will not surprise anyone who has followed the comedic drama of trying to pin down whether Godard will actually attend the Academy's Governors Awards dinner in November at the Hollywood & Highland Center.

At the same event, producer-director Francis Ford Coppola will receive the Irving G. Thalberg Memorial Award, and, in addition to Godard, actor Eli Wallach and historian-preservationist Kevin Brownlow have been chosen for honorary Oscars.

Despite a flurry of faxes, e-mails and couriered letters, Godard did not respond to the invitation for weeks, until some enterprising British reporters tracked him at his home in the Swiss town of Rolle.

Godard escaped the reporters, but Anne-Marie Mieville, his wife and work partner, said Godard was apparently disappointed that the honor would not be conferred at the main Oscars ceremony next February.

In any case, she said, Godard "is getting too old for this kind of thing. Would you go all that way just for a bit of metal?"

The French newspaper Liberation commented that it might be just as well if Godard stayed home, as his speeches "have become mysterious adventures in the country of language."

Nevertheless, the Academy remains officially upbeat, though hedging its bets by stating carefully that it "intends to bestow an honorary Oscar on M. Godard."

Though he may not like to travel, Godard continues to make new films with considerable vigor. His latest, "Socialism," screened at the New York Film Festival on Sept. 29 and will be shown again on Oct. 8.

Benjamin Ivry, a frequent contributor to the Forward, contributed to this article.

© Copyright 2010 Tribe Media Corp.

All rights reserved. JewishJournal.com is hosted by Nexcess.net. Homepage design by Koret Communications.

Widgets by Mijits. Site construction by Hop Studios

Labels:

anti-Semitism,

Breaking News on the Web,

Godard,

Oscars

Friday, October 8, 2010

Holocaust Studies / The final chapter

Haaretz.com

In a major new study, Daniel Blatman argues that on the Nazi death marches constituted a completely new stage in the history of the German genocide - in which murderous chaos had the upper hand.

By By Boaz Neumann

The Death Marches

The Final Phase of Nazi Genocide, by Daniel Blatman Yad Vashem Publications (in Hebrew ), 666 pages, NIS 98. Forthcoming in English in January 2011 (translation by Chaya Galai ) from the Belknap Press of Harvard University, 524 pages, $35

It's hard to come up with a new historical thesis about the Holocaust or Nazism, fields of study that are already jam-packed with researchers. But groundbreaking studies do appear every now and then, studies that offer a different interpretation of familiar historical events and can change the way we understand history. Daniel Blatman's "The Death Marches" is such a work.

The book examines the death marches, the chilling final throes of the Nazi genocide. Blatman, a professor of history at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, describes the hell imposed on those who appeared to have already experienced the worst of all fates, but were forced - exhausted, starving, broken, sick, dying - to move west on unpaved roads toward a ruined Germany, threatened from the west by the Allies and from the east by the avenging Red Army.

Blatman argues, justifiably so, that it is impossible to document all the death marches, which began in the summer of 1944 and went on until the collapse of the Third Reich. Nonetheless, in all the cases he examines, he succeeds in supplying very thorough descriptions of their twisting paths, the identities of the murderers and victims, and the circumstances of each.

Blatman is not satisfied, however, with simple descriptions of the marches, but also explains the dynamics behind them. Auschwitz, for example, was evacuated; at Gross-Rosen, in Lower Silesia, the march was a kind of murderous escape; at Stutthof, near Gdansk, Poland, the order was only partially carried out. None of these campaigns was methodical, as chaos reigned. When the prisoners arrived on German soil, they were considered even more dispensable than they were before. There was nowhere to house them and their economic value was nil. And so in February 1945, gas chambers were erected in Dachau, until then a concentration camp, but now turned into a death camp for all intents and purposes. At other camps, inmates were killed directly and indirectly, by means of starvation and epidemics. In this way, near the end of the Third Reich, Bergen-Belsen, in Lower Saxony, evolved from being the second most important transfer point into a major death camp. These facts furnish further proof of the modular capability of the Nazi camps, which could easily change their purpose from detention to punishment and, finally, to extermination.

More than genocide by more primitive means